Gentrification in Costa Rica beach communities is now a real issue as rents skyrocket, pricing out locals. Learn how nations like Italy and Portugal tackle similar struggles with innovative policies to balance tourism’s boom with the soul of ‘pura vida.’

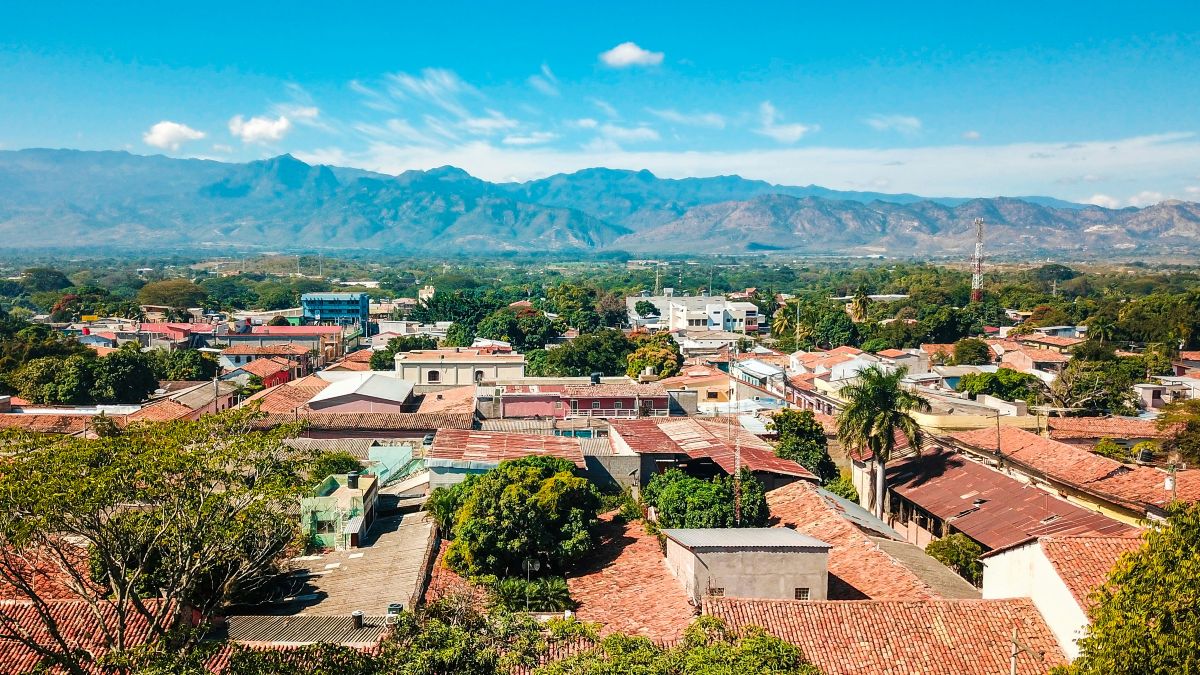

It’s no secret to anyone in Costa Rica that a backlash is brewing over cost of living and gentrification, especially in beach communities in Guanacaste and elsewhere. It feels like many of these places are losing their essence to gentrification and soaring rents.

Since the pandemic, housing costs have doubled, tripled, or even quadrupled in beach and tourist towns, making even modest spaces unaffordable for many local residents, who often work in tourism, serving foreign visitors. Homes and condos increasingly rent short-term on platforms like Airbnb rather than offer long term housing, pricing locals out of places like Nosara, Santa Teresa, and Tamarindo. The laid-back, inclusive vibe that drew tourists and expats in the first place is fraying as coastal communities turn exclusive, leaving many Ticos unable to live near or even visit their own beaches for the weekend. Resentment against foreigners is rising, with some political parties pushing xenophobic laws for leverage. In short, all this is the exact opposite of pura vida.

Without action, Costa Rica risks losing its magic. The country’s already seeing a tourism drop this high season, largely (although not totally) due to perceptions of being too expensive compared to other destinations. To paraphrase what many in the tourism industry are saying, Costa Rica could kill its golden goose and those eggs won’t come back anytime soon.

In the light of recent Costa Rica gentrification protests, we look at the situation from the point of view of locals, foreign residents, and the tourism industry 🇨🇷https://t.co/7CmkEqrQQF

— Central America Living (@VidaAmerica) January 20, 2025

A Look Around the World

But Costa Rica isn’t alone. The post-pandemic cost-of-living crisis has hit globally, and pushback against gentrification and the “Airbnb effect” is real. Below, we explore what other destinations have done and how their strategies could help reclaim the pura vida spirit that makes Costa Rica special.

Barcelona, Spain

Barcelona saw a massive backlash last year, with thousands taking to the streets in protest again gentrification. Some neighborhoods saw rents double from €700 to €1,200 monthly between 2000 and 2014, as tourism and Airbnb turned homes into vacation pads. In 2012, the city fought back with a €2.50 nightly tourist tax – tweaked over years to balance revenue and impact – raising €100 million by 2024, all funneled into 2,000 affordable housing units. A 100-inspector team enforces a strict 1% cap on short-term rentals, issuing €600,000 fines for illegal listings. The result? Rent growth slowed from 20% to 5% yearly by 2023, giving locals a lifeline.

It’s not perfect; some landlords exploit loopholes to dodge the rules. Still, it’s kept parts of the city from flipping entirely to tourist zones. For Costa Rica, where most short-term rentals operate unlicensed, this hits close. Licensing and taxing these rentals could generate millions to fund affordable homes in beach communities, helping Ticos stay put and keeping pura vida alive.

Mexico

Mexico’s coastal protection dates to its 1917 Constitution, born from fears of foreign land grabs after the Mexican-American War. Basically, foreigners are prohibited from owning land outright within 50 km of the shore. What they do instead is use fideicomisos, 50-year renewable bank trusts that keep ultimate control Mexican. In Baja California, some 66% of the coast falls under this system, balancing $2.1 billion in 2023 real estate investment with local priority. The system’s not flawless: wealthy buyers sometimes stack trusts or use proxies, and enforcement varies by region. Still, it’s kept many beach communities from becoming pure tourist enclaves, maintaining a mix of locals and visitors.

Thailand

Thailand’s approach dates to the 1954 Land Code Act: foreigners can’t own land outright, only lease it for 30 years (sometimes stretched to 90 via renewals) or buy condos capped at 49% of a building. In Phuket, a beach hub like Tamarindo, this has kept rent increases 50% below the unchecked surges seen in rivals like Bali, despite heavy tourism. Enforcement is relentless, and Thai proxies who get get caught face fines or jail, which keeps the system tight. It’s not without issues: developers sometimes flood the market with condos, and rural locals still struggle with costs. But Phuket’s beaches remain livable for Thais, not just tourists, avoiding a full gentrification takeover.

For Costa Rica, this offers a hint – leasing coastal land instead of selling could temper things down. It’s a way to balance tourism’s draw with local life, ensuring pura vida doesn’t slip away as beach communities turn exclusive.

Portugal

Rents in popular tourist parts of Portugal, like in Lisbon and the Algarve, have soared 65% since 2012, driven partly by the Golden Visa program launched that year to lure foreign investment. By 2023, 60% of housing in these areas flipped to tourist use, fueling a housing crisis. Facing backlash, the government restructured the visa, axing real estate as an option (once 89% of investments) while keeping paths like €500,000 fund investments or €250,000 cultural donations. A 2024 tax hike on short-term rentals aims for €50 million yearly to fund housing, pushing owners to lease long-term or live in properties.

In Costa Rica, there has already been talk of eliminating real estate as way to get residency through its $150,000 inversionista program. Following Portugal’s lead, it could redirect inversionista funds to local projects and tax rentals, nudging expats toward community roots and reviving pura vida as a shared reality, not a tourist catchphrase.

Italy

Italian tourist hubs like Florence have hit a breaking point in recent years with gentrification as short-term rentals flooded in, driving rents sky-high and locals out of historic centers. Since 2023, the government’s fought back: every rental needs a national registration code, and platforms like Airbnb must report data to enforce it; unregistered hosts face fines up to €8,000. Cities can cap rental numbers too, keeping housing for residents. It’s new, and enforcement’s still ramping up, but it’s slowing the takeover in places like Venice.

For Costa Rica, Italy’s model shows how registering rentals and leaning on platforms could help tame the chaos. It’s a direct hit at gentrification’s root, offering a path to keep beach towns inclusive for Ticos, not just tourists or expats.

Restrictions on land purchases, regulation of real estate agents, and securing access to beaches — these are some of the measures proposed by the collectives to stop the displacement of coastal communities in Guanacaste. https://t.co/VHhTHxeSIO

— La Voz de Guanacaste (@VozdeGuanacaste) March 15, 2025

Bringing Back Pura Vida

There’s no doubt right now that Costa Rica’s feeling the pinch. Tourist numbers are down, rents are up, and prices are through the roof. The growing resentment and sense of unease is getting real and could seriously damage Costa Rica’s reputation as a tourist destination if things don’t change. And if Costa Rica becomes unviable as a destination, then true poverty faces many communities which rely on tourism.

Short-term rentals are not the only cause of this situation, but they’re certainly a main driver of high housing costs in beach communities, where many people are at breaking point. We see the policies in Barcelona and Italy that register and tax short-term rentals, Mexico and Thailand that guard land, and Portugal that eliminates real estate purchases as a quick route to residency as ways to possibly solve this. That said, it’s never a one-size-fits all solution with these things.

Perhaps Costa Rica can implement some of these policies into a plan to stay whole. The aim isn’t to shut out tourists and expats; it’s to keep local people in their own communities. Without some action, the tensions created by gentrification in Costa Rica could pull the nation too far apart.